I’ve always had a soft spot for cryptozoology, the pseudoscientific field of fascination with unsubstantiated creatures. Who can resist the romantic allure of the Loch Ness Monster that supposedly dwells in the Scottish Highlands, the chupacabra of Hispanic America, or Point Pleasant’s own Mothman? Cryptozoology’s marriage of ‘kryptós’ and ‘logos,’ translated directly to ‘hidden knowledge,’ reminds us that the world undoubtedly possesses secrets that have not yet been revealed. Beyond the astonishing fervour that a surprising number of conspiracy theorists continue to demonstrate, cryptozoology’s broader appeal reflects an understanding that nature still possesses the ability to surprise and delight us.

If there is any cryptid who rivals Disney’s Mickey Mouse or Nintendo’s Mario as an immediately recognisable mascot, it is almost certainly Bigfoot, alternatively known as Sasquatch, the hairy, hulking, bipedal beast that patrols both American and Canadian folklore. As with the Himalya’s own Yeti, or Abominable Snowman, on the other side of the globe, North America’s Bigfoot demonstrates a continued fascination with ape-like and Neanderthalic humanoids that can be traced throughout all our species’ history.

The Sasquatch has become an important emblem of North American cultural identity, with its origins rooted in the legends and folklore of the Sts’ailes, a community indigenous to Chehalis, in British Columbia, who ‘passed down songs and stories about sasq’ets, a supernatural slollicum, or shapeshifter, that protects the land and people’ (Kadane 2022). As so often occurs with indigenous mythologies, the fascination surrounding these wildmen was soon Anglicised and eventually, after several well-publicised hoaxes by North Western loggers and foresters, translated into a veritable commercial empire.

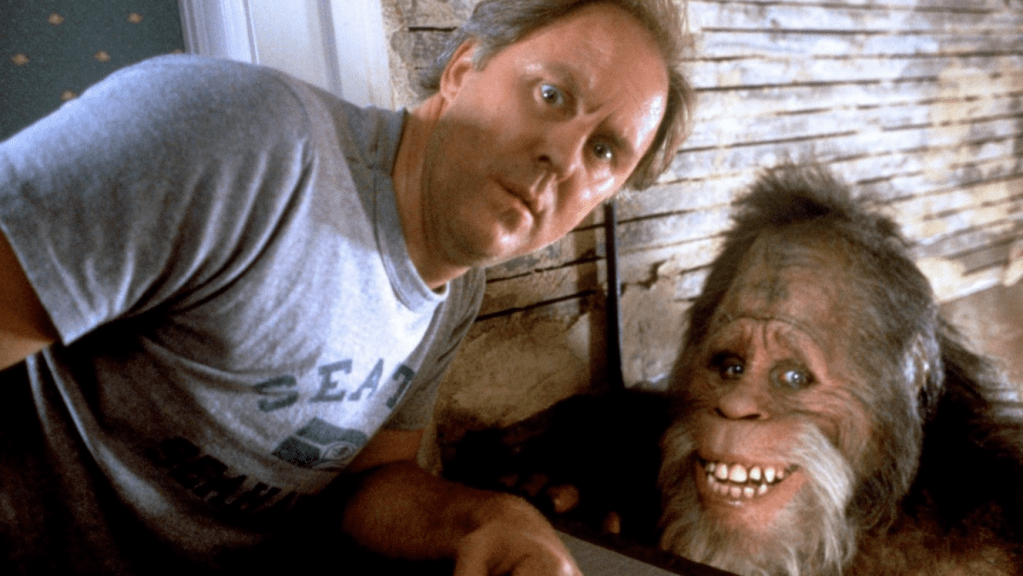

Following a tidal-wave of media interest that reached fever pitch in the late 60s and 70s, Bigfoot has certainly found itself well-represented in film. From horror movies such as Bigfoot (1970), Night of the Demon (1980) and Abominable (2006), which depict its sightings ending in violence and carnage, to saccharine family-friendly adventures such as Cry Wilderness (1987), Bigfoot: The Unforgettable Encounter (1995) and Little Bigfoot (1997), America’s love of the hairy cryptid appears relatively boundless. It goes without saying that the Academy-Award-winning masterpiece Harry and The Hendersons (1987) deserves an article of its own for featuring John Lithgow begrudgingly learning to befriend one of the creatures after hitting it with his station wagon.

All in all, for contemporary audiences, bigfoots and sasquatches – let’s settle on our plurals now – have come to signal a sense of instability and incompatibility in our own relationship to nature. Whether they depict the cryptid as a rampaging monster or benevolent beast, these are films that collectively draw upon the shared fears and anxieties that are produced when we feel a sense of removal from the natural order we associate with the wilderness.

Sasquatch Sunset (2024), one of the more recent attempts to engage in this shared mythology, wears its cult credentials proudly on its furry sleeves. Directors and brothers Nathan and David Zellner had previously dabbled in bigfoot filmmaking with Sasquatch Birth Journal 2 (2010), an absurdist short that is almost entirely constructed around a single take of one of the creatures giving birth while bracing itself among the branches of a tree.

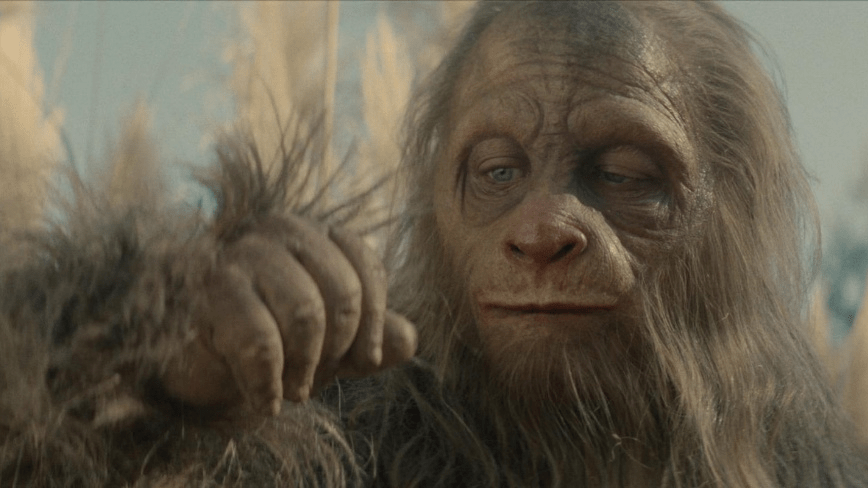

Sasquatch Sunset maintains this singular focus by featuring no human characters or discernible dialogue. Throughout its entire theatrical running time, audiences are treated to performances of Riley Keough, Jesse Eisenberg, Christophe Zajac-Denek, and Nathan Zellner himself, elaborately costumed as a family of nomadic bigfoots who go about grunting, whooping, and huffing through the wilderness.

The Zellners’ film relies on a strange concoction of crude scatological humour, sexual encounters, and full-frontal sasquatch nudity with an eerily beautiful depiction of the American wilderness. Life as a bigfoot is represented as comically visceral and bawdy, yet underscored by a wordless and ever-present sense of existential melancholy. If this is a film that either intrigues or repels you, you can probably already tell. Sasquatch Sunset is undeniably a passion project produced by like-minded collaborators who vibe with its tonal shifts and absurdist humour, with Eisenberg even footing some of the production budget himself when an initial financier backed out (Salisbury 2024).

The film’s most remarkable quality is that it is framed as a fabricated nature documentary, taking inspiration from the Patterson-Gimlin footage of 1967 that supposedly captured images of a bigfoot striding purposefully through Six Rivers National Forest. ‘It’s one of the most famous pieces of film in film history,’ David Zellner would argue, describing the fascination that he and his brother developed after watching the footage in an episode of the 1970s paranormal investigation series In Search of… hosted by Leonard Nimoy (ibid).

Sasquatch Sunset might best be defined as a kind of cryptid mockumentary, playfully mashing up conventions of satire and documentary just as its subject stalks the boundaries of science and pseudoscience. While paranormal investigation series such as Finding Bigfoot (2011-2018) have helped perpetuate the creature’s myth, the Zellners’ film is presented as if it were a David-Attenborough-esque nature documentary, minus the presenter’s dulcet narration. Similarly, the film’s drama is depicted as emerging naturally from the four sasquatches as they meander around their woodlands, rather than conforming to the tightly plotted regimes of scripted filmmaking.

Sasquatch Sunset’s ridiculous central premise, that of human performers stomping about in bigfoot costumes, satirises the seemingly unimpeachable authority that Matthew Brower argues is often falsely attributed to wildlife photography: a ‘nonintrusive, environmentally friendly activity that shows proper respect for the fragility of nature’ (2011: xiii). Our media’s representations of the natural world have, of course, always been the product of deliberate construction. Disney’sWhite Wilderness (1958), for example, grotesquely featured filmmakers carolling a group of lemmings off a cliffside to emulate mass migration, while, more recently, the BBC defended its decision to record scenes of a polar bear giving birth in a Dutch zoo for its Frozen Planet (2011) series (Burrell 2011).

The refusal of Sasquatch Sunset’s subjects to behave in a manner that might see them appropriate for wide-spread documentation is undeniably part of their charm. Scenes in which they variously consider having sex with a hole in a log after being rebuffed by a potential mate, throw a recently birthed placenta to distract a hostile mountain lion, or embark on a hallucinatory rampage after consuming a psychoactive cocktail of berries, aren’t just silly, they are amusing precisely because they are delivered in the straight-faced and erudite delivery of the wildlife documentary. By revisiting Patterson and Gimlin by way of Attenborough, the Zellner brothers identify, as with all good mockumentaries, an appropriate target for ridicule. The sasquatches’ antics remind us that nature is, in contrast, equal parts funny, tragic, grotesque, and absurd.

Sasquatch Sunset undermines another significant fallacy that Brower identifies, one that acts as a lynchpin of the Bigfoot myth. This is the argument that wildlife footage and photographs ‘function as a substitute for a real nature that the images themselves assert is impossible for humans to enjoy’ (2011. xiv). Brower’s claim here is that the pleasure of watching animals in the wild is often credited to the act of looking into a world that we believe we are excluded from. Just as Bigfoot’s status as a wildman emphasises our own seemingly distinct identity as modern and civilised beings, so too does the nature documentary’s erasure of signs of human observation help to reinforce the myth that our species is ultimately separated from the wildlife that surrounds us.

This perspective is often masked under noble intentions, that of conservationism, yet belies an anthropocentric arrogance that defines much of our species’ experience. The idea that humans are different, distinct, and no longer bound to a natural order is everywhere. René Descartes famously labelled species different from our own as ‘automata,’ machine-like beings incapable of thought or reason (Brown 2018), while Aristotle and Giovanni Pico della Mirandola respectively cited humanity’s seeming rationality and self-determinism as evidence of our apparent distinctiveness (Aristotle 1925 [circa 350 BCE]: X.7, Pico della Mirandola 2016 [circa 15th c.]).

Humanity’s innate belief in its own exceptionalism is not aided by the fact that we are the last surviving Hominina species. Our developing understanding of taxonomic threads such as Neanderthals, Denisova, Luzonesis and Floresiensis actively remind us that our direct siblings have only been extinct for a brief span of our existence. The mystique of the ‘missing link’ is a testament to the perceived gulf that can, with enough evidence, be breached. That, surely, is part of the appeal of Bigfoot; the idea that we might bump into a fellow family member were we to delve deep enough into the surrounding wilderness. We might, we imagine, not be as alone as we first assumed.

Attempting to explain his movie’s ambitions beyond its gross-out humour, David Zellner would argue that he wanted to subvert the tradition of films featuring Bigfoot, as well as similar monsters and cryptids, that privilege a human perspective and point of view: ‘we really wanted to have it reversed where the humans assume that position, where they’re the mysterious alien life form basically that you’re only exposed to to a certain degree’ (qtd. in Frank 2024). As such, Sasquatch Sunset reframes its bigfoots from being the supporting and antagonistic figures most predominantly depicted in media, into full-ledged protagonists. Audiences are then invited to play at being ethologists, deciphering the nature of their relationships, reactions, and rituals entirely non-verbally.

Watching Keough playing the sole female in the group, we gradually come to understand her resolve to keep her family together despite the hedonistic impulses of Zellner, whose territorial and aggressive personality quickly gets the better of him. The grunts and huffs of Eisenberg’s curious sasquatch teach us that he is attempting to dabble with basic arithmetic, although he struggles to make it past the number three, while Zajac-Denek’s youngster of the group carefully watches and learns from his elders’ interactions.

Sasquatch Sunset’s positioning of its audiences amongst its hairy subjects reflects how our relationship to animals is ordered by the very acts of spectatorship and subjectivity that film-watching itself is defined by. As Murray Smith argues, character engagement is constructed through various processes of ‘recognition, alignment, and allegiance,’ or, rather, the human need to find a point of identification through which we can experience a narrative (2022: 73). The team behind the film were well-aware of the potential problems that they might encounter when dramatising a story that features a cast entirely buried beneath fur suits and thick latex prosthetics. Eisenberg enlisted the movement coach Lorin Eric Salm, whom he had worked with when playing Marcel Marceau in Resistance (2020), and the Zellners ran a ‘Sasquatch School’ to help the performers cultivate a consistency between their behaviour and mannerisms (Nemiroff 2024).

Despite the already laborious make-up process, the decision was made to avoid using contact lenses, with David Zellner explaining that ‘we wanted the actors’ real eyes to be seen because so much information was going to be communicated through them. Especially with Riley, because she’s so expressive. She has these bright blue eyes that pop and telegraph so much info.’ (qtd. in Salisbury 2024). Zellner’s comment that it is the performer’s eyes that act as the gateway to a meaningful connection recalls popular discussions of similar opportunities to develop human-animal empathy. As Jane Goodall wrote of her first close encounter with the apes that would forever shape her life and work, ‘staring into the eyes of a chimpanzee, I saw a thinking, reasoning personality looking back’ (1999: 2).

Whether through sight gags, such as the compulsion of Keough’s sasquatch to repeatedly sniff at her fingers after scratching her crotch, or scenes of despair, as experienced when a newborn infant suffers from asphyxiation, the film’s seemingly raw and observational nature emphasises its connection between observer and subject. The film’s chief delight is reconciling the sasquatches’ strange behaviour with relatively primal impulses that we, as humans, are all familiar with. More sinisterly, this process acts as an opportunity to question our species’ tendencies towards anthropomorphism, and the dangerous consequences that occur when our ability to empathise is primarily motivated by whether or not we can position ourselves alongside the identities of those different to us.

As well as reflecting questions of human experience and subjectivity, the myth of Bigfoot evokes the concerns of countless species that are on the brink of extinction due to human encroachment upon their habitats. The Zellners don’t need to articulate directly that this clan may be the last of their kind as we are all too familiar with the fact that the sasquatches’ elusive aura is sustained by their scarcity. Folklorist Joshua Blu Buhs connects the creature to various tales of similar spirits and wildmen, arguing that ‘sasquatch became a symbol of the environmental movement, a myth created to re-enchant the world and make its preservation a sacred task’ (2009: 234)

An existential sense of loneliness seeps throughout Sasquatch Sunset as successive misadventures see their number slowly dwindle. At various points in their journey, we watch as the family ritualistically drums upon tree trunks with branches, beating out a call that echoes through the forests. Prominent Bigfoot trackers who have heard such noises, called tree-knocking, coming from woodlands have argued that the sound likely acts as a means of communication by the species (Carrol Sain: 2020). Whatever the case, when Sunset Sasquatch’s protagonists send out their call, there is no answer but silence.

Shot in Six Rivers National Forest, the same region that the Patterson-Gimlin footage was captured, Sasquatch Sunset is something of a pilgrimage for the Zellner brothers. The landscape photography of cinematographer Mike Gioulakis is suitably awe-inspiring, depicting acres of coniferous forests and towering redwoods that sweep across the Klamath Mountains into a seemingly endless expanse of greenery.

The stalking image of Bigfoot has become what ethnohistorian Robert Walls describes as ‘a kind of charismatic megafauna’ (2022), indivisible from the greater ecology of the Pacific North West within which it lives. Eisenberg would consider these themes a primary motivator for his interest in the fictional cryptid, stating that sasquatches ‘represent our connection to nature and other creatures in a mythological—or perhaps not mythological—way’ (qtd. in Frank 2024).

Throughout most of the film, the Zellners depict this wilderness as a liminal space, completely devoid of any markers that we can grasp upon to locate ourselves within a specific period of time. That is, until the film establishes its final act, and the sasquatches encounter a road. The family react in abject horror at the enormous and alien strip of tarmac that carves through their territory, urinating and defecating upon it to express their displeasure. Soon after. they quizzically attempt to decipher the strange ‘x’ marks that have been branded upon several trees, flee from a forest fire that bellows smoke in the distance, and stumble upon an abandoned campsite where they rummage through the decidedly human artefacts that have been left strewn about.

The finest sequence in the film is undoubtedly the one in which Keough’s sasquatch lifts a boombox aloft and, fiddling with the device, plays a tape which has Erasure’s hit, ‘Love to Hate You’ (1991), recorded upon it. Keough stands as if in a trance as the synth-pop tune blares from the boombox’s speakers. When the refrain of ‘Waoh Oh Oh Oh!’ begins, she appears captivated by what are, significantly, the first human voices that we have heard in the entire film. They are almost certainly the first that she has heard in her entire life. Her response, when she finally moves, is one of primal rage and loathing, and she proceeds to destroy every constructed human object that is within her reach.

This is the moment where the gulf between the sasquatches and their human audience is at its largest. They are completely unaware of the nature of the strange world they have entered, while we, of course, are able to experience it with easy familiarity. Yet, although the dramatic irony experienced through our differing understanding might be distinct, the anger directed at humanity’s encroachment of the forest is certainly not.

In April of this year, soon after taking office for his second term, Donald Trump rescinded various environmental protections that applied to over half of the U.S.’s national forests. The administration cited attempts to control wildfires as the cause of their decision (Brown 2025), but fingers were quickly pointed at Trump’s desire to cut lumber imports and his statement that ‘we have massive forests. We just aren’t allowed to use them because of the environmental lunatics who stopped us’ (qtd in. Milman 2025).

Researchers and state foresters have argued clearly and vocally that the strategy of preventing wildfires via increased logging requires careful and precise management if it is not to worsen the situation, and can only be of potential aid if done selectively (Cornwall 2025). Such recent changes in policy are only the tip of an ecological and biological collapse that decades of climate change and industrialisation have wrought. Sasquatch Sunset might dramatise the moment that its family of bigfoots stumble upon the Anthropocene, but the tipping point that announces the irreversibility of our own relationship to our forests is, sadly, already far behind us.

However, just as the myth of Bigfoot encourages the human propensity to anthropomorphise the natural world into a human form, so too are there dangers to overly-sentimentalising our wildernesses. The cryptid’s commercialisation throughout popular media in the 1970s brought with it what Joshua Blu Buhs defines as a particularly middle-class fantasy of the natural world: ‘the paradise that Bigfoot guarded was a place where leisure was valued over work,’ he writes, ‘where walkers and hikers and backpackers knew the world better, survived the world better than those who worked in it’ (2013: 45).

The particularly bourgeois tendency to imagine the wilderness as a place that should be cleansed of human influence threatens to erase the countless communities, trades and businesses that are inexorably tied to its well-being. The current administration’s rolling back of environmental laws and heavy tariffs have been announced as the remedies for the struggling logging towns scattered throughout the Pacific North West, but forestry experts contend that doing so does little to assist their long-term survival (McNichols 2025). Similarly, plans to entirely close the U.S. Forest Service’s headquarters in the region under the guise of cutting public spending will effectively dismantle the vital presence of rangers, firefighters, ecologists, and researchers who help maintain the area (Ehrlich 2025).

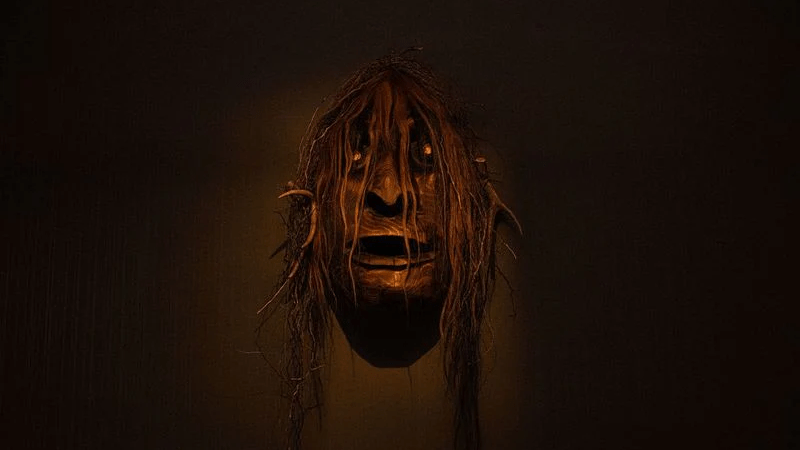

The ecosystems that the legend of Bigfoot encourages us to engage with are, to put it mildly, extraordinarily complex. Sentimentalism and anthropomorphism are not the answers to the region’s survival, but empathy for the realities of the beings that live there is essential. It is notable, therefore, that Sasquatch Sunset concludes on imagery that complicates the mythologies that it helps to advance. The surviving bigfoots never encounter a living human throughout the duration of their long journey, but they do conclude it by staring up at a strange effigy that our species has created in their own image.

This endpoint is a 25-foot statue called ‘Oh Mah Bigfoot’ that stands at the entrance of Willow Creek-China Flat Museum, self-proclaimed ‘Gateway to Bigfoot Country’ (‘Willow Creek’ 2025). This encounter, static though it may seem, enables the Zellners to flip the position of observer and subject that has sustained the production so far. The camera lingers as Keough and Zajac-Denek stare, dumbfounded into the statue’s face, seeking recognition in the warped, uncanny totem that stands alone within this utterly alien world. In our desperate attempt to give form to ideas and mythologies that we do not truly understand, humanity’s attempts to represent the sasquatches mean little to the creatures themselves. As Margaret Atwood wrote in a poem she once penned about the ever-mysterious cryptid, ‘sasquatch can never be known: he can teach you only about yourself.’ (1970: 20).

Head Image: Sasquatch Sunset, Bleeker Street, 2024.

Abominable. 2006. D. Ryan Schifrin, Film, USA: Freestyle Releasing.

Aristotle (1925 [c.350 BCE). The Nicomachean Ethics: Translated with an Introduction. Translated by David Ross. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Atwood, Margaret. 1970. ‘Oratorio for Sasquatch, Man, and Two Androids,’ Poems for Voices, Toronto: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation.

Frozen Planet. 2011. TV Series, October 26 – December 28, UK: BBC.

Bigfoot. 1970. D. Robert F. Slatzer, Film, USA: Ellman Enterprises.

‘Bigfoot.’ 1977. In Search of…, TV Episode, April 28, USA: Alan Landsburg Productions.

Bigfoot: The Unforgettable Encounter. 1995. D. Corey Michael Eubanks, Film, USA: PM Entertainment.

Brower, Matthew. 2011. Developing Animals: Wildlife and Early American Photography. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Brown, Deborah J. 2018. ‘Animal Souls and Beast Machines: descartes’s mechanical biology’, in Peter Adamson, and G. Fay Edwards (eds) Animals: A History, New York: Oxford Academic: 187-210.

Brown, Matthew. 2025. ‘Trump administration rolls back forest protections in bid to ramp up logging,’ Independent, April 4: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/donald-trump-joe-biden-forests-congress-great-lakes-b2727730.html.

Buhs, Joshua Blu. 2009. Bigfoot: The Life and Times of a Legend, Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Buhs, Joshua Blu. 2013. ‘Camping with Bigfoot: Sasquatch and the Varieties of Middle-Class Resistance to Consumer Culture in Late Twentieth-Century America,’ The Journal of Popular Culture 45:1: 38-58.

Burrell, Ian. ‘BBC denies fake polar bear scene was misleading,’ Independent, December 13: https://www.independent.co.uk/hei-fi/news/bbc-denies-fake-polar-bear-scene-was-misleading-6276283.html.

Carrol Sain, Johnny. 2020. ‘Finding bigfoot: in the woods in search of North America’s great, wild ape,’ Hatch, September 25: https://www.hatchmag.com/articles/finding-bigfoot/7715127

Cornwall, Warren. 2025. ‘Trump wants to log more forests. Will it really help prevent wildfires?’ Science, April 17: https://www.science.org/content/article/trump-wants-log-more-forests-will-it-really-help-prevent-wildfires.

Cry Wilderness. 1987. D. Jay Schlossberg-Cohen, Film, USA: Visto International Inc.

Ehrlich, April. 2025. ‘Time is running out to weigh in on Forest Service overhaul that would close Pacific Northwest headquarters,’ Oregon Public Broadcasting, September 27: https://www.opb.org/article/2025/09/27/forest-service-northwest-headquarters-closure/.

Smith, Murray. 2022. Engaging Characters: Fiction, Emotion, and the Cinema, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Finding Bigfoot. 2011-2018. TV Series, May 29 – May 27, USA: Animal Planet.

Frank, Allegra. 2024. ‘There’s Much More to Sasquatch Sunset Than Piss and Poop,’ Daily Beast, April 20: https://www.thedailybeast.com/obsessed/sasquatch-sunset-is-about-so-much-more-than-piss-and-poop/.

Goodall, Jane and Berman, Phillip. 1999. Reason for Hope: A Spiritual Journey. New York: Warner Books.

Harry and The Hendersons. 1987. D. William Dear, Film, USA: Universal Pictures.

Kadane, Lisa. 2022. ‘The true origin of Sasquatch,’ BBC, July 21: https://www.bbc.co.uk/travel/article/20220720-the-true-origin-of-sasquatch.

Little Bigfoot. 1997. D. Art Camacho, Film, USA: Republic Pictures.

‘Love to Hate You.’ 1991. Erasure, Song, Chorus, UK: Mute Records.

McNichols, Joshua. 2025. ‘Could Trump’s tariffs bring back the Pacific Northwest lumberjack?’ Oregon Public Broadcasting, July 20: https://www.opb.org/article/2025/07/20/washington-lumberjack-trump-tariffs/.

Milman, Oliver. 2025. ‘Outcry as Trump plots more roads and logging in US forests: “You can almost hear the chainsaws,”’ The Guardian, October 6: https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/oct/06/trump-logging-forests.

Nemiroff, Perri. 2024. ‘Riley Keough Opens Up About Having a Sasquatch for a Director,’ Collider, January 27: https://collider.com/sasquatch-sunset-riley-keough/.

Night of the Demon. 1980. D. James C. Wasson, Film, USA: VCII, Inc.

Pico Della Mirandola, Giovanni. 2016 [circa 15th c.]. ‘Oration on the Dignity of Man’, translated by Richard Hooker, Brians: https://brians.wsu.edu/2016/11/14/pico-della-mirandola-oration-on-the-dignity-of-man-15th-c-ce/

Resistance. 2020. D. Jonathan Jakubowicz, Film, USA, UK & Germany: IFC Films.

Salisbury, Mark. 2024. ‘How Jesse Eisenberg “saved the day” by helping to fund Sasquatch Sunset,’ Screen Daily, February 15: https://www.screendaily.com/features/how-jesse-eisenberg-saved-the-day-by-helping-to-fund-sasquatch-sunset/5190541.article.

Sasquatch Sunset. 2024. D. Nathan and David Zellner, Film, USA: Bleecker Street.

Walls, Robert. 2022. ‘Bigfoot (Sasquatch) legend,’ Oregon Encyclopedia, September 7: https://www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/bigfoot_sasquatch_legend/.

‘Willow Creek.’ 2025. The Humboldt County Visitors Bureau: https://www.visitredwoods.com/listing/willow-creek/118/.