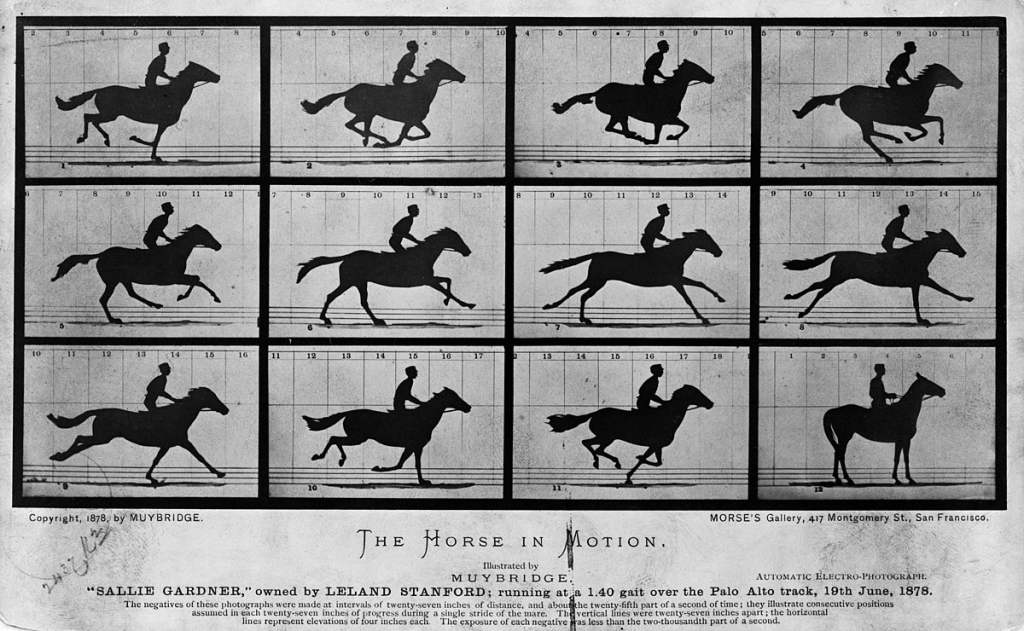

Have you seen this image before? If you have, it’s almost certainly because someone has attempted to illustrate an example of early photographic motion to you. These distinct silhouettes of a galloping horse are what we first call to mind when we think of cinema’s birth. Before we imagine Louis Le Prince’s family at a garden in Roundhay, Leeds (1888), before Fred Ott sneezes for William Dickson at Thomas Edison’s movie studio (1894), before the Lumière brothers’ train pulls up to its station (1896) and before Georges Méliès memorably embeds a rocket ship in the eye of the man in the moon (1902), all our visual media seems to trace us back to this horse, seemingly hanging in mid-air, as its legs gallop beneath it.

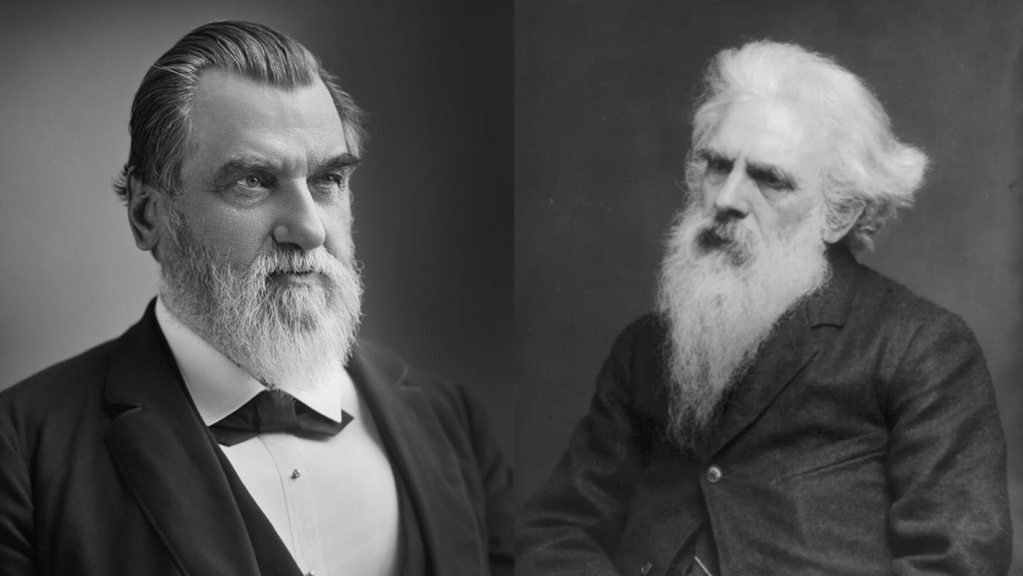

Most of us are aware that these images were captured by Eadweard Muybridge, the photographic pioneer who would publish them throughout the 1880s. Muybridge had been commissioned by the industrialist and politician Leland Stanford to help him determine the exact gait of a horse and settle the issue as scientifically as possible. It’s a reminder to us that the film industry first arose out of nineteenth-century technological experimentation and was often driven by attempts to study the natural world and document it for posterity. The image of the horse wasn’t only the product of this curiosity; it was its inspiration.

The power of film’s historical gaze forces us to consider the extent that its foundational images play a hugely significant role framing, focusing upon, and erasing the lives of those that it ostensibly attempts to capture. We would, after all, do well to remember that, in his time as Governor of California, Stanford perpetuated the suppression and elimination of the state’s Native American communities (Madley 2016), and referred to Chinese immigrants that had sought labour during the gold rush as ‘an inferior race’ (qtd. In Sandmeyer 1973: 43). Before the publication of his historical plates, Muybridge had already proved himself to be a similarly controversial figure, having shot and killed the man he believed was having an affair with his wife, a woman half his age at the time of their marriage. The all-too-familiar moral whiplash of encountering the attitudes of the past through those of the present is one that is experienced by anyone who expresses any degree of historical curiosity. If history teaches us anything, it is that, rather than avert our gaze, we possess a responsibility to consider how these uncomfortable truths are embedded in both our most treasured myths and, therefore, our contemporary surroundings.

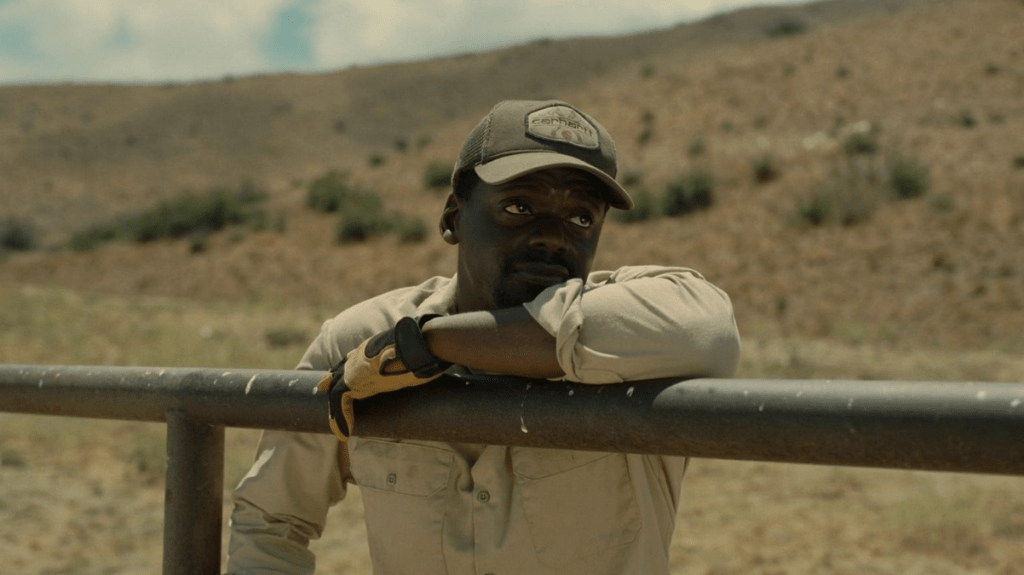

Jordan Peele calls this history into question in his sci-fi horror movie Nope (2022), offering a powerful indictment of the erasure of Black bodies from cinema’s history by utilising Muybridge’s images. Plate 626 (1887), of mare Annie G. being ridden by an unnamed Black rider, is used in the film to illustrate the voices, perspectives and experiences forever condemned to silence. Engaging with similar debates, art history professor John Ott used Muybridge’s photographs to consider the barriers and restrictions facing a Black American workforce: ‘boxing and horse racing were two fields where they could make a name for themselves and could mingle with white Americans,’ he states, arguing that such roles also had the effect of positioning Black sportsmen within racist associations of animalistic performance’ (qtd. in Han 2022).

As for the horses, their value was great enough that their names were indeed recorded. Sallie Gardner, Abe Edgington, Mahomet, Annie G., and Occident, as well as others, were all owned by Stanford and had their names listed alongside their respective plates. As standard and thoroughbreds, their names were worthy of record and signalled their status as creatures with immense commercial value. Lyman Horace Weeks’ historical account, The American Turf, tracks well-trained racehorses being sold for multiple thousands of dollars in this era, while those whose costs of upkeep outpaced their ability to perform were, instead, ‘shot as useless’ (1898, p. 92).

The exploitation of racehorses is as well-documented as it is harrowing. While it was in the best interests of owners such as Stanford to keep their top-achieving animals fit, well-fed and cared for, their status as investments to be capitalised upon was without question. Bone and tendon injuries are endured from over racing, pain-based techniques using whips, spurs and harsh-bits are implemented to advance speeds, heritable weaknesses are driven by genetic exploitation, while the animals can find themselves wracked by musculoskeletal damage, respiratory conditions, bleeding lungs, gastric ulcers, and chronic lameness.

Such conditions are inflicted through breeding and training, well before the sheer danger involved in racing itself is encountered. The Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority (HISA) reported that, in 2024, the fatality rate of breaking the gate in America could be measured at 0.90 of 1,000 (Carroll 2025). Although an improvement over previous years, this statistic confirms that almost one in a thousand horses will not survive the races that they endure, let alone the harrowing experience of cruelty, drug-use and slaughter experienced off the track.

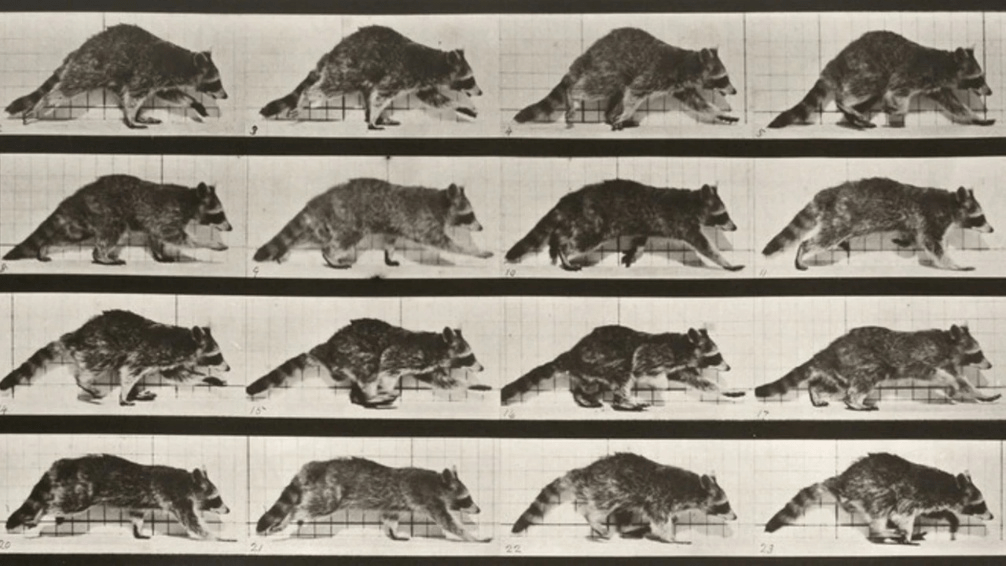

Beyond their commodification within the sporting world, Muybridge’s images remind us of the vivisectional status of animals within our society. In both the twenty-first and nineteenth-centuries the autonomies of non-human animals are treated as inconsequential if their lives may be put to the service of our scientific enquiries. As Annie Dwyer argues of Muybridge’s photography, ‘the camera not only captures but actively constructs animal life as a mechanical phenomenon, stripped of animacy or agency’ (2022: 34). Dwyer positions Muybridge’s photographs of horses alongside those of humans: men, who he depicts in the act of ‘carpentry, masonry, and blacksmithing,’ and women, who he comparatively captures performing domestic tasks such as ‘sweeping, washing, and scrubbing floors’ (ibid.: 44). Human and horse alike find their bodies reduced to anatomical projections of expectations regarding identity and labour.

Similarly, Stanford’s racehorses are swept up in Muybridge’s catalogue of railroads, dockyards and plantations, transformed into icons of industrialised capitalism that careens forwards with forceful momentum. In An Introduction to Animals and Visual Culture (2012), Randy Malamud contends that ‘the horses lose something in this transaction’ (66). ‘Muybridge’s photographs starkly alienate animals from their natural context,’ he writes, ‘exuberantly reframing them in his own amazing new technological discourse of visual culture. The animals appear against a backdrop of numbered scales and grids, the more convenient to chart and graph them’ (ibid.: 66).

Capturing them within his lens, Muybridge turned Stanford’s galloping horses into icons of the birth of an entire industry. Their emergence into the world of the moving image carried with it the sense of dignity, endurance, gender, nation, Empire, chivalry, and industry that our species has projected upon equines for numerous centuries. In the very-same decades that Muybridge’s work capitalised upon these attitudes, women such as Caroline Earle White and Anna Sewell were actively transforming conceptions of equine welfare through, respectively, the foundation of the American Anti-Vivisection Society and the publication of Black Beauty (1877). Our relationships to horses had become a means through which our entire civilisation and engagement with the natural world could be understood.

Much of the history of film scholarship has taught us that to photograph, to gaze and to look is not a passive activity. Instead, to distil an identity into a moving image is to engage in dynamics of power and dominance. To represent the lives around us in our visual media is to define and control them through our own understandings and prejudices. Muybridge’s images act as a branch of natural photography that treated animals as subordinated tools to further humanity’s industrial and scientific enterprises.

In his book, Developing Animals: Wildlife and Early American Photography (2011), Matthew Brower argues that these photographs ‘have been seen as offering us access to an otherwise inaccessible “truth” of animals. But this access has come at the cost of devaluing the unmediated experience of animals,’ asserting that such imagery ‘does not provide unmediated access to the animals depicted, but rather it structures its audience’s understanding of animals in particular ways’ (xix).

Humanity’s desire to watch and look at other creatures is an innate part of our species’ nature, especially as we find ourselves living in an ever-modernising world that seems to pull us further and further away from the realm of seemingly natural experience. Just as our ancestors daubed great beasts on the stone walls that surrounded their hearths, the photographic technologies we now utilise are products of our animalistic ingenuity, and allow us to leave an indelible imprint upon our cultures. While those cave paintings were rendered in flickering firelight, our own cinematic images of animals offer powerful opportunities to reflect upon our relationship with nature. Significantly, they also allow us to leave a lasting impression of how this bond might be remembered.

Head Image: Muybridge, 1878.

Brower, Matthew. 2011. Developing Animals: Wildlife and Early American Photography. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Carroll, Rory. 2025. ‘Horse racing-US horse racing deaths fell in 2024, regulator says,’ Reuters, February 20: https://www.reuters.com/sports/horse-racing-us-horse-racing-deaths-fell-2024-regulator-says-2025-02-20/.

Dwyer, Annie. 2022. The Incorporation of the Animal: Eadweard Muybridge’s Animal-Machine. Transpositiones 1:2, 33-54.

Fred Ott’s Sneeze. 1894. D. William Dickson. USA, Film: Edison Manufacturing Company.

Han, Yoonji. 2022. ‘From a murderous affair to an anonymous Black jockey, the true story behind the moving pictures in Jordan Peele’s Nope,’ Business Insider, August 2: https://www.businessinsider.com/nope-black-jockey-pictures-muybridge-horse-in-motion-history-2022-8.

L’Arrivée d’un train en gare de La Ciotat. 1896. D. August and Louis Lumière. France, Film: Société Lumière.

Le Voyage dans la Lune. 1902. D. Georges Méliès. France, Film: Star Film Company.

Madley, Benjamin. 2016. An American Genocide: The United States and the California Indian Catastrophe, 1846-1873. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Malamud, Randy. 2012. An Introduction to Animals and Visual Culture. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Nope. 2022. D. Jordan Peele. USA, Film: Universal Pictures.

Roundhay Garden Scene. 1888. D. Louis Le Prince. UK, Film: Louis Le Prince.

Sandmeyer, Elmer Clarence. 1973. The Anti-Chinese Movement in California. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Sewell, Anna. 1877. Black Beauty: His Grooms and Companions, the Autobiography of a Horse. London: Jarrold and Sons.

Weeks, Lyman Horace. 1898. The American Turf: An Historical Account of Racing in the United States. New York: The Historical Company.