Guillermo del Toro loves monsters. If there is any connective thread that runs through the director’s work, it is the very-same that the zealous Frankenstein uses to stitch together the patchwork flesh of his own creation. Whereas the latter would become horrified by the monstrous appearance of his life’s work, del Toro hopes to enthral us with his representations of outcasts who are demonised for their rejection of social norms.

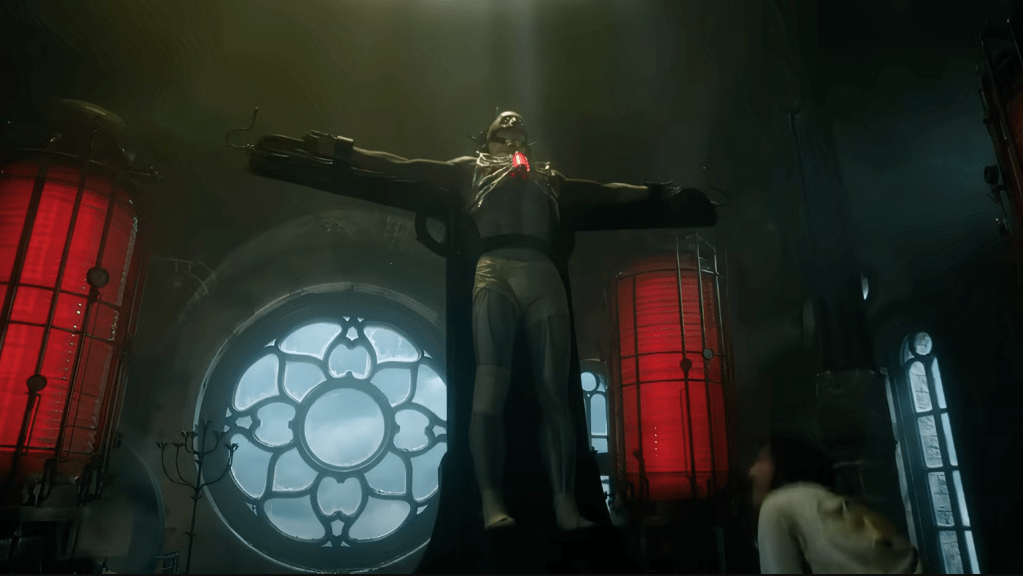

The anticipation surrounding his adaptation of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818) has been fuelled by its seeming inevitability. ‘The creature of Frankenstein,’ del Toro would argue, speaking of Boris Karloff’s portrayal, “was a more beautiful martyr figure than Jesus with the exposed fracture. And I started adoring him’ (qtd. in Sweet 2025). This veneration is on full display in his adaptation, not only through his casting of the impossibly chiselled Jacob Elordi, but through the dialogue of Elizabeth, Mia Goth, who questions the incredulous Frankenstein, Oscar Isaac, ‘What if, unrestrained by sin, our creator’s breath came into its wounded flesh directly?’ (Frankenstein, 2025).

Del Toro’s messianic depiction of his Creature reflects his ongoing attempts to relate the special-effects driven spectacle of genre cinema through stories that feature marginalised individuals that are villainised for their social difference. So too has Mary Shelley’s own work continually been opined as a significant opportunity to explore nineteenth-century attitudes towards issues such as sexuality, gender, and social strata from an almost endless array of perspectives.

As George Haggerty argues in ‘What is Queer about Frankenstein?’ ‘there is nothing normative about the relationship between Frankenstein and his creature: the almost by-definition dysfunctional family relations are transgressive from the start’ (Haggerty 2016: 116). The scientist’s own fervour, after all, is defined by his willingness to deviate from expected roles regarding reproduction in the pursuit of the ‘perfect’ male form, while the resultant Creature is defined by its inability to find social acceptance.

One act of defiance that the Creature claims for itself is its choice to refrain from eating meat, stating to his creator that “My food is not that of man; I do not destroy the lamb and the kid to glut my appetite; acorns and berries afford me sufficient nourishment. (Shelley 1818: 149). Notably, Carol J. Adams linked the Creature’s diet to feminist scholarship by dedicating an entire chapter of her book, The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory (1990), to its exploration. ‘Vegetarianism, like feminism,’ she writes, ‘is excluded from the patriarchal circle, just as Mary Shelley experienced herself as being excluded from the male circle of artists of which she saw herself a part’ (Adams 1990, 119).

The Creature’s revelation of his plant-based diet has several different functions in Shelley’s novel. Being a veggie, for him, is a means of persuading Frankenstein to create a female mate. His reasoning is that, if he were to have some companionship, he would have no incentive to harm anyone and could live out the remainder of his life beyond civilisation’s reach. A rejection of carnism, therefore, is an attempt to evidence both his moral dignity and his desire for social withdrawal.

The idea that vegetarianism is a sign of monstrous deviance is everywhere in our contemporary culture. Think for a moment, of the many vegan and vegetarian characters who are depicted as fanatics or oddballs, smug moralists, or even dangerous psychotics. Tom Clancy, for example, seems to find the prospect of such lifestyles utterly baffling, depicting them in Rainbow Six (1998) as a sure-fire means of identifying extremist eco-terrorists hell-bent on humanity destruction. Worse still, refusing to eat meat is frequently depicted as a rejection of presumed maleness. ‘The vegan monster offers a monstrous embodiment of human desires,’ writes Emelia Quinn, ‘threatening, as a result, existing discourses of meat-eating that work to shore up and insatiate a particular ideal of white, Western masculinity’ (Quinn 2021: 17).

So, how did these culinary contexts make their way into Frankenstein? As the child of pioneering women’s rights campaigner Mary Wollstonecraft and political author William Goldwin, Mary Shelley was profoundly influenced by the social circles that she encountered throughout her life. She would rub shoulders with several Romantic-era advocates for vegetarianism, including Joseph Ritson, John Frank Newton and, notably, Percy Bysshe Shelley, the writer with whom she would elope and begin a tumultuous relationship.

Percy Shelley himself would produce a pro-veggie pamphlet in which he argued that, were it not for the Promethean theft of fire, we might not be so willing to tuck into the flesh of other animals: ‘It is only by softening and disguising dead flesh by culinary preparation that it is rendered susceptible of mastication or digestion, and that the sight of its bloody juices and raw horror does not excite intolerable loathing and disgust’ (Shelley 1813: 13). Food, as it were, for thought.

By imagining another Promethean creation similarly falling from grace, Shelley’s writing acts a cornerstone of the Regency and Victorian-era Romantics who helped to develop criticisms of industrialisation, the potential hazards of over-agriculturalisation and inequality driven by starvation and malnutrition, developing many of the country’s first animal welfare laws. When Michael Owen Jones collated several articles that explore the relationship between food and culture, for example, he chose to title it Frankenstein Was a Vegetarian: Essays on Food Choice, Identity, and Symbolism (2022).

With this history in mind, where does this leave Guillermo del Toro’s recent production, and his own obsession with the vegetarian monster that haunted Shelley’s imagination over two-hundred years ago? The director had stated in 2015 that watching The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) had ‘made me a vegetarian for four years’ (qtd. In Alexander 2015), and he has similarly delivered a graduation commencement speech for the entirely vegan MUSE School in Los Angeles, where he argued that “we’re living in a world that is really on the brink in so many ways, ecologically, socially, full of injustice that seems to change, then comes back’ (MUSE School CA 2019).

It’s in del Toro’s own body of work, however, that it becomes clear that his monstrous protagonists are all, in some way or another, shaped by issues surrounding speciesism and humanity’s fascistic approach to animal welfare. It is no coincidence that when the Creature of this film first encounters human civilisation, it is through an encounter of hunters stalking prey. Alone for the first time and wandering disorientated through the woods, Frankenstein’s creation encounters a deer peacefully grazing upon a bush. Approaching tentatively, he retrieves some berries and eats one himself, before extending his palm out to the animal in an invitation to feed. Bang! Suddenly this moment of serenity is shattered when hunters kill the deer with a single shot of a rifle.

Despite being a product of man-made intervention, del Toro frequently positions his Creature as a force of nature, having a group of cottagers refer to him as ‘The Spirit of the Forest’ when he offers them unseen benevolence. Even when held captive within the bowels of the great stone tower that Frankenstein uses as his laboratory, the Creature is fascinated with the few elements of the natural world that he can interact with from his confinement, marvelling at leaves as he sets them upon water, watching them float down a small gulley that passes through his otherwise barren basement.

If the Creature’s identity is defined by his relationship to nature and vegetarianism, then Frankenstein’s is as carnivorous as one can imagine. It is an act of meat eating that establishes the toxic nature of his parents’ relationship and the scientist’s subsequent desire to penetrate the natural order of life and death. Charles Dance, coldly demands that his pregnant wife, Mia Goth in her second role, eat a piece of bread that has been dipped in the red juices of a particularly rare cut of meat, explaining to her that ‘the salts will enrich your blood.’

Describing the shocking amount of flesh that covers many of the film’s sets, Oscar Isaac would describe his laboratory as a ‘meat banquet’ (qtd. in Hall 2025). Indeed, Frankenstein’s workshop opens into a butchers’ market that is decorated with a row of pigs’ heads hanging on a rail, carts of meat, and even a bucket of bones and offal. When the scientist invites his soon-to-be benefactor, Henrich Harlander, Christoph Waltz, inside, the audience is treated to a close-up of the latter hopping over a puddle of blood that has spilled down the street. It should be remembered that Shelley herself utilised similar imagery in her own novel, with her scientist stating that ‘The dissecting room and the slaughter-house furnished many of my materials; and often did my human nature turn with loathing from my occupation’ (Shelley 1818: 55).

Although they seem dissimilar, both Frankenstein and his creation are bound by their shared desire to understand the circumstances of their life, birth, and eventual death. What distinguishes the Creature’s gentle observations from his creator’s unempathetic zeal is their treatment of other living beings. It’s impossible to watch the film without comparing the scientist’s cruel conduct towards his creation, pulling him up in chains, barking instructions and beating him with a metal rod to real-world acts of animal mistreatment and captivity. Notably, when the scientist begins preparing for his final confrontation with his creation, he is asked by a merchant what he is hunting; his reply is, simply, ‘big game’.

Frankenstein then, is not a character that del Toro depicts as one who would have any interest in animal lib. Instead, it is Elizabeth that allows the director to offer comparative acts of compassion. The dual casting of Mia Goth as Frankenstein’s deceased mother and unrequited paramour allows her to represent the life and love that the scientist is impotently unable to dominate. It is Elizabeth who challenges Frankenstein’s assumptions that humanity’s infliction of pain on other animals can be justified due to their seeming lack of sentience. ‘What is pain,’ Elizabeth proposes, ‘if not a mark of intelligence?’

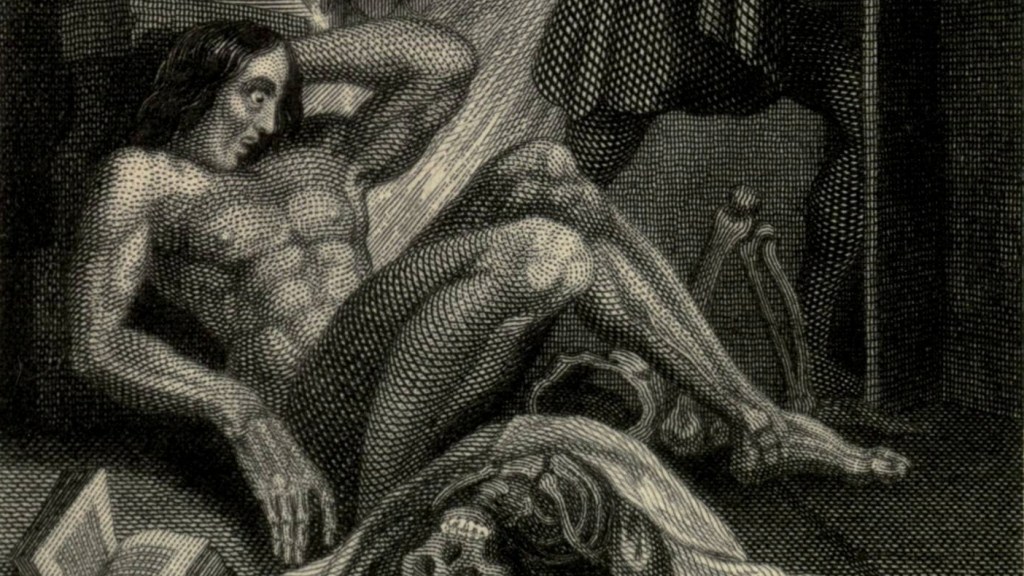

Mary Shelley’s most enduring legacy is, perhaps, the rage expressed by Frankenstein’s ‘monster’ once it realises that its existence will not be tolerated by humanity. Some have chosen to explore this anger as an expression of the many traumas that the author endured throughout her life, especially the patriarchal injustices that she was subjected to as an intellectual (Tillotson 1983: 175). Others have continued to find courage in her Creature’s indignant wrath. ‘My Words to Victor Frankenstein above the Village of Chamounix: Performing Transgender Rage,’ for example, acts as a powerful example of Shelley’s novel being transformed into a performance piece designed to ‘harness the intense emotions emanating from transexual experience – especially rage – and mobilize them into effective political actions’ (Stryker 1994: 237).

As for del Toro, his speech at the plant-based and sustainably-driven campus reflected similar concerns. ‘One of the energies you have as young people is rage. Most people tell you not to use it, to put it away, to be nice,’ he would claim, “I say make peace with it and use it. Be enraged at what you are inheriting. Be enraged at what you cannot do and what’s possible before and change it […] What makes you “stubborn” and “impossible” makes you tenacious’ (MUSE School CA 2019).

The power of Mary Shelley’s creation has resonated across two centuries, in far greater effect than those of her male contemporaries. Del Toro’s newest incarnation of her Creature reminds us that rage is a natural response to injustice and that if we want to continue defining humanity through our seemingly humane natures, then we drastically need to rethink our relationship to the natural world that we exploit for the sake of our own pride, ambition, and gluttony.

Head Image: Netflix, 2025

Adams, Carol J. 1990. The Sexual Politics of Meat: A Feminist-Vegetarian Critical Theory. New York: Continuum.

Alexander, Thomas. 2015. ‘[Interview] Guillermo del Toro on Serenading Crews, Silent Hills and Crimson Peak,’ October 7, Bloody Disgusting: https://bloody-disgusting.com/news/3364524/interview-guillermo-del-toro-on-serenading-crews-silent-hills-and-crimson-peak/.

Clancy, Tom. 1998. Rainbow Six. New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Frankenstein. 2025. D. Guillermo del Toro. USA, Film: Netflix.

Hall, Gerrad. 2025. ‘Oscar Isaac on creating Frankenstein’s doctor — and giving him a ‘rock star’ quality,’ September 4, Entertainment Weekly: https://ew.com/oscar-isaac-frankenstein-doctor-victor-rock-star-exclusive-11801021.

Jones, Michael Owen. 2022. Frankenstein Was a Vegetarian: Essays on Food Choice, Identity, and Symbolism. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi.

MUSE School CA. 2019. ‘2019 MUSE School Graduation Commencement Speech,’ June 26, YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NokdAkdjzFw&t=95s.

Shelley, Percy Bysshe. 1913. A Vindication of Natural Diet. London: Smith & Davy.

Shelley, Mary. 1818 [2013]. Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus. London: Penguin Books.

Sweet, Matthew. 2025. ‘How Netflix turned Frankenstein Catholic,’ November 11, The Telegraph: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/films/0/how-netflix-turned-frankenstein-catholic/.

The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. 1974. d. Tobe Hooper. USA, Film: Bryanston Distributing Company.

Tillotson, Marcia. 1983. ‘“A Forced Solitude”: Mary Shelley and they Creation of Frankenstein’s Monster,’ Julian E. Fleenor ed., The Female Gothic. Montreal: Eden, 176-175.

Stryker, Susan. 1994. ‘My Words to Victor Frankenstein Above the Village of Chamounix: Performing Transgender Rage,’ A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 1:3, 237-254.

Quinn, Emelia. Reading Veganism: The Monstrous Vegan, 1818 to Present. Oxford: Oxford University Press.