The recent release of H is for Hawk (2025) has encouraged me to revisit Ken Loach’s Kes (1969), an extraordinarily empathetic production that needs little introduction. As well as helping to cement British social realism as one of the country’s most significant cultural movements, Loach’s body of work provides UK cinema with a degree of conscience, articulated through the exploration of debates such as immigration, colonialism, poverty, workers’ rights, and social justice. As the director’s second feature film, Kes arguably remains one of his finest calls to compassion, an unflinching, yet tender and poetic exploration of a young Yorkshire lad who finds fleeting fulfilment in the art of falconry.

The boy himself is Billy Casper, convincingly played by 14-year-old David Bradley. Billy suffers physical and mental abuse at both school and home, and, despite his distress at the prospect of working down the pits, there seems to be little opportunity for him to break free of the exploitative grind that determines his present and will surely govern his future. Frustrated, alone and with no emotional support, he resorts to petty criminal acts to escape the tedium of life in the amalgam of mining communities surrounding Barnsley, South Yorkshire, that the film is set and shot within.

Kes’ social significance has been well-documented and covered by an endless array of critics, authors, and film historians. As Jacob Leigh highlights in the loftily-titled The Cinema of Ken Loach: Art in the Service of the People, ‘Kes protests against an educational system which fails to recognise individual talent, and it suggests that this is a consequence of a capitalist society which demands a steady supply of unskilled manual labour’ (Leigh 2002: 64). In this article, I’ll be engaging with discussions that explore how these themes are expressed through a key icon of the film’s cultural authority and relevance: the eponymous avine himself.

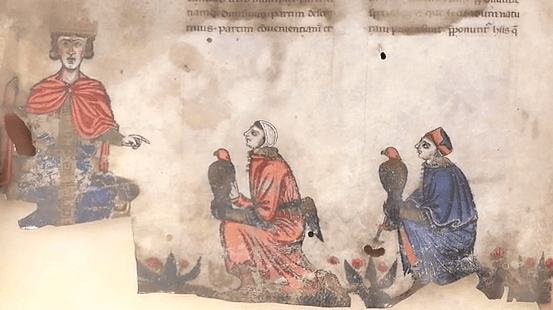

Kes’ use of falconry subverts and develops perceptions of class and social status that can be traced through centuries of avicultures that have spread around the world. When UNESCO recognised the practice as an Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2010, it did so in recognition of the indelible ties that link birds of prey to various cultures’ antiquities, spanning thousands of years across several continents. For the Bedouin peoples of the Middle East and North Africa, raptors were integrated into all strata of their nomadic life, signposting discipline, heritage, and identity, as well as providing a practical means of subsistence hunting (Wakefield 2012: 280). In Medieval Europe, their purpose was more recreational, but nevertheless still signalled social position.

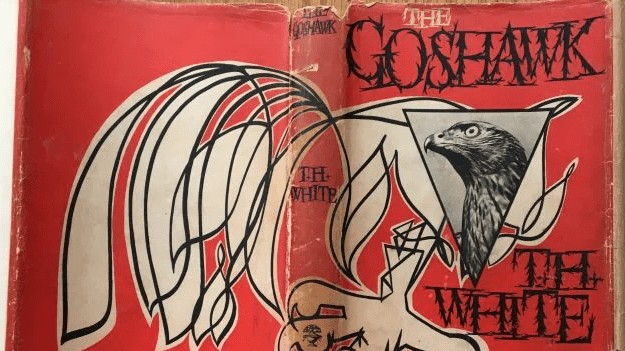

Much of this history is foreshadowed in the name of the book that Kes adapts, A Kestrel for a Knave (1968), by Barry Hines. Hines’ novel will be familiar to generations of Brits who read his work on their GCSE English syllabus, and was based on the escapades of his own brother, Richard, who, after being inspired by T. H. White’s The Goshawk (1951), had trained a kestrel himself while growing up in Hoyland Common, South Yorkshire.

Hines’ title was borrowed from The Book of Saint Albans (1486), otherwise known as The Book of Hawking, Hunting, and Blasing of Arms, which provides a hierarchy of raptors based on social positioning, assigning those on the lowest rung, the knave or servant, the small Eurasian kestrel (Berners 1486 [1881]). The art of falconry, then, reflects recognition of the social restrictions that limit Billy’s horizons, but also provides him with the tools that, for a time, allows him to defy them.

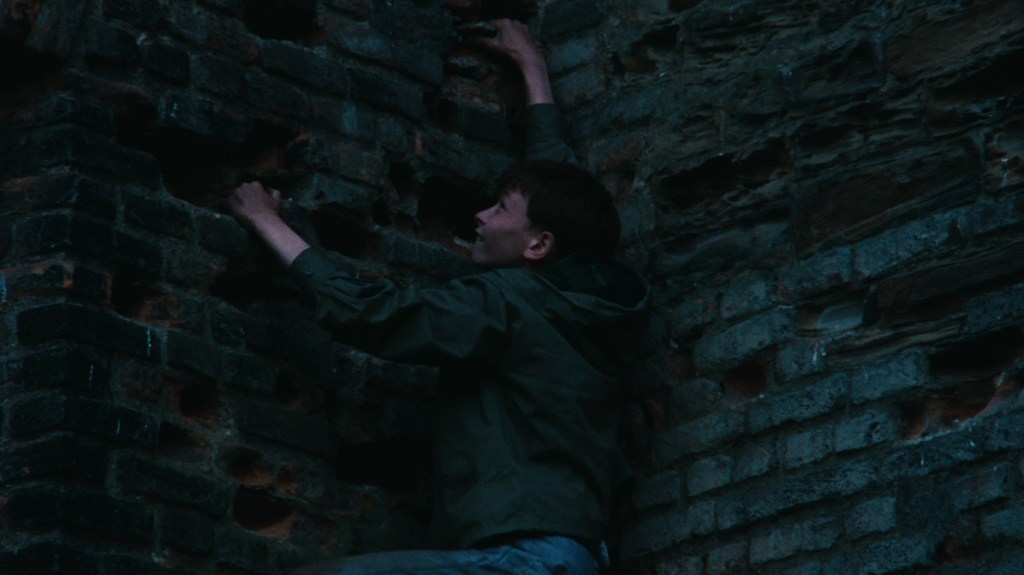

For Billy, training Kes affords him a freedom and autonomy that he drastically lacks both at home and school. The cunning that he demonstrates as a troublemaker, filching milk and eggs from carts, is granted a productive outlet and he is finally able to engage with a practical and intellectual challenge that stimulates him. It is his own curiosity that draws Billy to the kestrel’s nest in the ruins of Tankersley Old Hall, and he mimics the actions of his real-world counterpart, Richard Hines, by furtively trespassing under the cover of darkness and stealing a nestling from its shelter in the stonework (Hines 2016: 165).

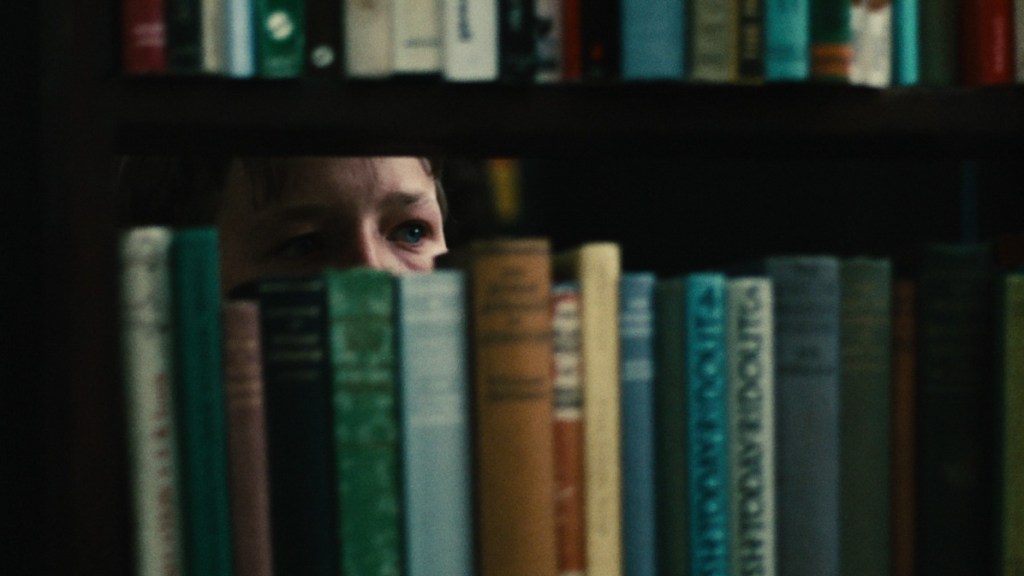

Blocked at almost every turn by authority, Billy’s attempt to acquire both knowledge and resources are systemically restricted. With no assistance, he has to get by on his own initiative and intuition to begin training the bird. He is denied membership to his library due to his dirty hands and the lack of authorisation from a parent, and, with no money, Billy resorts to stealing a book on falcons from a second-hand shop. His elder brother, Jud, Freddie Fletcher, mocks him and treats it with disdain: ‘you must be crackers,’ he says, ‘I could understand if it were money, but chuff me, not a book!’

Billy’s ability to engage in the art of falconry is not only a sign of his maturity and growth; it is the product of a Promethean act of rebellion against an educational system that is failing him on every conceivable level. Theft remains the boy’s only recourse. Whether it be the removal of Kes from his nest or the pilfering of a book, everything that Billy holds dear must be self-gained.

Simon Golding associates this misfortune with the tripartite system that, throughout mid-twentieth-century Britain, ensured that pupils were segregated based on their performance in their examinations at the ages of eleven to twelve. ‘Billy Casper,’ he writes, ‘was a victim of the 11-plus. A government directive that turned out, who passed the exam, prospective white-collar workers, fresh from grammar schools, into jobs that were safe and well paid. The failures, housed in secondary modern schools, could only look forward to unskilled manual labour or the dangers of the coal face’ (2014: ii).

If Billy’s acquisition of Kes and his book on falconry are the product of his own tenacity and resourcefulness, then his eventual skills reflect his patience and competencies. Training a wild bird is no small feat, and little by little, we watch as Billy learns to leash his bird and guide it through the air using his lure. Karl-Heinz Gersmann and Oliver Grimm argue that, while our fascination with hawks and falcons may have been born from an envious fascination with their ability to glide and kite through the air, stooping down suddenly in pursuit of their prey, it is ultimately the patience required to handle and train them that underlines their significance as cultural symbols. ‘In the history of domestication, birds of prey hold a special position,’ they write, ‘strictly regarded, they are not domesticated; they can only be trained to grow accustomed to the presence of humans, which is time-consuming and calls for patience’ (2018: 19).

This patience, for many cultures, becomes emblematic of both wisdom and effective leadership, meaning that to properly train a falcon walks hand in hand with the qualities required to be an adept ruler. Kes, therefore, helps to elevate Billy’s sense of self-worth and gives him an opportunity to prove his mettle. Writing for Sight & Sound, Isabel Stevens marvels that Loach had never considered the symbolic meaning of the kestrel itself, but argues that it is impossible not to, with hindsight, interpret the bird as representative of stymied potential. In opposition to the fact that ‘the fate of many working-class boys like Billy lies underground in one of Barnsley’s collieries,’ she argues that Kes demonstrates ‘mastery of the sky, soaring and swooping high above’ (2021).

Significantly, Billy’s skill in falconry not only affords him self-earned agency, but also, to his great surprise, gains him a degree of dignity and respect that he has never received before. One of his teachers, Mr. Farthing, Colin Welland, is impressed enough to watch him train Kes after school, remarking ‘Well done, Casper. The most exciting thing I’ve ever seen in my life. Great!’ The boy is even encouraged to develop the confidence to talk with authority about a subject of which he now has specialist knowledge, standing in front of his class, answering questions from his curious schoolmates, and explaining equipment such as jesses and a creance.

As well as affording Billy his own autonomy and pride, the young boy’s respect for his kestrel is undeniable. He is particularly affronted by the suggestion that it might be considered a domesticated pet. ‘Is it heck tame! Hawks can’t be tamed,’ he explains enthusiastically, ‘they’re manned. It’s wild and it’s fierce and it’s not bothered about anybody. Not bothered about me, right. That’s what makes it great.’

In Kes, Billy has discovered a creature worthy of the adoration that is denied to him at home. In counterpoint to Jud’s domineering bullying and his mother’s exhausted indifference, the kestrel’s wild nature acts as preferable source of emotional support and companionship. Sean Nixon notes in Passions for Birds: Science, Sentiment and Sport (2022), that Billy thrills ‘at being connected to its more-than-human world’ and contends that while the boy ‘identifies with the independence and wildness and violence of the kestrel’s life, he does not want to dominate it and own it in any proprietorial sense’ (185).

Kes’ majestic characteristics transfer to the textual qualities of Loach’s film as well. His flights provide both Billy and his audience respite from the kitchen-sink aesthetic so often associated with British social realism. There can be no denying the natural beauty surrounding the villages of South Yorkshire, not yet excavated by the coal fields that Billy’s brother toils within. The sight of boy and kestrel training in the neighbouring countryside, captured by cinematographer Chris Menges, provides the film a serenity and grace that is far removed from the hubbub of Billy’s domestic and school life.

Mr. Farthing immediately notices a sense of awe and sanctity when watching the bird in flight. ‘It’s as if they’re flying in a pocket of silence,’ he says while Billy houses Kes in his mews, ‘have you noticed how quietly we’re speaking? As if we’re frightened to raise our voices, a bit like shouting in church.’ Spatially and audibly, the world seems to slow down when Billy flies his kestrel, accompanied by the lilting tones of a sole flute, composed for the film by John Cameron.

These are sublime moments captured in a movement of realist filmmaking most familiarly represented through that of gritty miserabilism. Of his own research into the film, David Forrest states that Kes ‘shows us that places like Barnsley – often overlooked and maligned in mainstream culture – are sites of humour, creativity, beauty, and potential. Far from being pessimistic, Kes points to a hopeful way of imagining Britain as formed from the unique cultural contributions of its regions, towns, and cities’ (Barton 2024).

The virtues to be found in the tale of Billy and Kes had not gone unnoticed. The Walt Disney Company had expressed interest in adapting Hines’ novel, with the condition that Kes survive and Billy be provided a happy ending (Stevens 2021). Loach’s Kes might possess idyllic moments but, like the young boy’s attitude towards his bird, is certainly not sentimental and ultimately concludes, like the book, in tragedy. Jud, angry that his brother didn’t place a bet as he was instructed, kills Kes in callous retribution. For Jud, the kestrel’s death is rightful recompense for the loss of winnings that equated to a week’s work he could have avoided down the pits. For Billy, the loss is catastrophic and he responds in impotent fury. The film’s final moments see the boy tenderly stroking Kes’ feathers, before digging a makeshift grave and burying him.

As for the fate of the real animals used during filming, Richard Hines, acting as technical adviser, had caught and trained three kestrels to be used during filming, taking them from their nests at Tankersley Old Hall Farm (Hines 2016: 164). David Bradley would remember spending numerous days at the Hineses’ house in Hoyland, steadily learning to work with the birds that had been named Freeman, Hardy and Willis, after the shoe-store chain. ‘Freeman is the kestrel that flies fairly low to ground, whereas Hardy flies from a fairly high vantage point and he would swoop down at me,’ Bradley would explain decades later, ‘Willis, unfortunately, was completely neurotic and psychotic and we couldn’t use him’ (Loach et al. 1999).

Barry Hines would describe the process as being complex and painstaking: ‘It’s not like working with a trained dog. A kestrel has to be the right weight,’ he would explain, ‘they only fly if they’re hungry so we would weigh them before a scene and if they were too heavy they had to wait to shoot the scene’ (ibid.). In a bid to heighten Bradley’s emotions before shooting the film’s conclusion, Loach and his team informed the boy that they had needed to kill one of the kestrels to use on screen. ‘I was really miffed when it came to do that sequence,’ the actor recalled, ‘it was quite upsetting’ (ibid.). The filmmakers would assure Bradley after filming that the body used had been sourced from a bird that had died from natural causes, with Freeman, Hardy and Willis being hacked back to the wild when they were no longer needed (Stevens 2021).

Kes’ arrival on screen coincided with a renewed public interest in aviculture, with Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962) and J. A. Baker’s The Peregrine (1967) both gaining success as natural science books in the years before its release. This public interest was timely and vital due to the fact that kestrel numbers, alongside many species of wild birds, were experiencing a steep decline. Use of organochlorine pesticides had devastated their population after the Second World War, while ever-intensifying methods of farming made a similarly destructive impact on their habitats throughout the 1970s (UK Gov 2025).

The profound influence of T. H. White’s evocative writing on Richard Hines, passed in turn onto Billy Casper, has proved similarly long lived. It has, however, been significantly reframed since its publication. Helen Macdonald, author of H is for Hawk (2014) is plain in her admiration for White’s prose, but distances herself from his falconry techniques which, she argues, expressed far more of his relationship to himself and his repressed sexuality that it did the needs of his goshawk: ‘He couldn’t be himself,’ she states, ‘so he wanted to associate with the hawk because it was all the things he wanted to be – powerful, sadistic’ (Barkham 2014). Indeed, White would describe depriving the creature of rest, ensuring it was exposed to extreme stress, and, in moments of anger, wishing to inflict upon it the ‘extreme torture it deserved’ (White 1951: 115). The depictions of animal care in Kes, and for that matter, H is for Hawk, are, thankfully, more ethically robust than White’s. Both are tender without overly anthropomorphising their subjects. The greatest unease to those outside of falconry circles is undoubtedly the visceral manner with which the training of these captive animals requires the hunting of those that remain in the wild.

The practice of wild take, that undertaken by both Richard Hines and Billy to acquire their kestrels, has also significantly changed over the last half century. A 2025 report by Natural England observed that the state receives almost no requests for licences to retrieve birds of prey from their nests in the United Kingdom, and that, instead, falconers now entirely rely on captive breeding to obtain the creatures (Natural England 2025). One interviewee stated that when they were a child ‘everybody went out and collected eggs and robbed nests. Kids don’t do that anymore. They identify nests or they jump on their webcam and watch a peregrine breeding its young and it’s enough, and that’s great’ (ibid).

The Wild Animal Welfare Committee welcomed the news that the review recommended the cessation of such licenses, stating firmly that ‘wild caught individuals are likely to experience an increased likelihood of motivational frustration, a high likelihood of negative affective states (such as fear) and behaviours consistent with experiencing stress in captivity’ (Wild Animal Welfare Committee 2025).

Even with the end of licensed wild take, current conservation laws are consistently flouted in ways that the British government is struggling to police. A 2025 report by The Guardian observed that UK-based breeding facilities of falcons had grown from approximately 27 in the 1980s to a current tally of 160, all of which have ties to Middle Eastern markets that are driving an underground industry of illegal capture and smuggling of wild birds (Weston 2026).

Half of these facilities are considered non-compliant with contemporary UK legislation, driving an international trade within which a well-bred falcon can cost upwards of tens of thousands of pounds. ‘This Bedouin tradition has evolved into a spectacle of wealth and prestige to meet the tastes of the modern Gulf elite,’ Phoebe Weston reports, ‘the cold climate of northern Europe is considered the ideal for creating tough, fast birds, and British-bred birds from established lines carry additional prestige’ (ibid).

The mistreatment of birds of prey is not isolated to illegal acts of capture, trade, and smuggling. The RSPB recently highlighted the widespread killing of threatened species such as golden eagles, goshawks and hen harriers that has gone almost completely unprosecuted throughout the United Kingdom (RSPB 2024). ‘In the past 15 years, only one person has been jailed,’ their report claims, ‘and of all individuals convicted of bird of prey persecution-related offences between 2009 and 2023, 75% were connected to the gamebird shooting industry’ (ibid). Conservationist Ruth Tingway’s blog, Raptor Persecution UK, acts as a harrowing, but vital, attempt to track such acts of violence, and is an essential resource for understanding the scale of human-inflicted damage upon these remarkable creatures.

Acts of hunting, trading, and smuggling continue to have devastating consequences for species of birds that, for centuries, have been utilised by humanity as icons of nobility and dignity. Their training and use for sport encourage the same discussions that are necessitated whenever our species chooses to capture or domesticate other animals for our own interests. Our love of raptors has ensured that they are ferried around the country for handling experiences, kept captive in bird display centres, and tethered for the entertainment of the public. It is significant that Kes’ socialist power, as an exploration of hierarchies that restrict and curtail, should be articulated through the bond between a boy and his bird. Billy’s respect for Kes’ autonomy reflects the cultural contradiction that lies at the heart of our fascination with falcons and hawks. His admiration, like ours, also brings with it the discomfort found when wildness is expressed through fettered wings.

Head Image: Kes, United Artists, 1969.

Baker, J. A. 1967. The Peregrine, London: Collins.

Barkham, Patrick. 2014. ‘Helen Macdonald: ‘I Ran to the Hawk Because I Was Broken and Grieving,’ The Guardian, August 1: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2014/aug/01/helen-macdonald-interview-hawk-grief.

Barton, Sean. 2024. ‘Kes Recognised as British Classic and Landmark in World Cinema,’ University of Sheffield, May 7: https://sheffield.ac.uk/news/kes-recognised-british-classic-and-landmark-world-cinema.

Berners, Juliana. 1486 [1881]. The Book of Saint Albans: https://archive.org/details/cu31924031031184/mode/2up.

Carson, Rachel. 1962. Silent Spring, Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Forrest, David. 2024. Kes, London: Bloomsbury.

Gersmann, Karl-Heinz & Grimm, Oliver. 2018. Raptor and Human: Falconry and Bird Symbolism Throughout the Millennia on a Global Scale, Hamburg: Wachholtz Verlag.

Golding, Simon. 2014. Life after Kes, Clacton on Sea: Apex Publishing.

H is for Hawk. 2025. D. Philippa Lowthorpe, UK & USA: Lionsgate.

Hines, Barry. 1968. A Kestrel for a Knave. London: Michael Joseph.

Hines, Richard. 2016. No Way But Gentlenesse: A Memoir of How Kes, My Kestrel, Changed My Life, London: Bloomsbury.

Kes. 1969. D. Ken Loach, United Kingdom: United Artists.

Leigh, Jacob. 2002. The Cinema of Ken Loach: Art in the Service of the People, London: Wallflower Press.

Loach, Ken, Garnett, Tony, Hines, Barry, Bradley, David & Welland, Colin. 1999. ‘A Typical Reaction Was A Snigger… I Was Making A Film About the Wrong Kind of Bird,’ The Guardian, August 29: https://www.theguardian.com/film/100filmmoments/story/0,4135,77579,00.html.

Macdonald, Helen. 2014. H is for Hawk, London: Jonathan Cape.

Natural England. 2025. ‘Summary of Natural England’s Position on Wild Take Licensing for Falconry and Aviculture,’ gov.uk, March 6: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/taking-birds-of-prey-from-the-wild-for-falconry-and-aviculture-outcome-of-review/summary-of-natural-englands-position-on-wild-take-licensing-for-falconry-and-aviculture.

Nixon, Sean. 2022. Passions for Birds: Science, Sentiment and Sport, London: McGill-Queen’s University Press.

RSPB. 2024. ‘Illegal Bird of Prey Killing Must End, Urges RSPB Birdcrime Report,’ RSPB, October 22: https://www.rspb.org.uk/media-centre/illegal-bird-of-prey-killing-must-end.

Stevens, Isabel. 2021. ‘Kes: Big Screen Classics,’ Sight & Sound, September: https://bfidatadigipres.github.io/big%20screen%20classics/2022/08/09/kes/.

UK Government; Department for Environment, Food & Rural Affairs. 2025. ‘Wild Bird Populations in the UK and England, 1970 to 2024,’ gov.uk, September 23: https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/wild-bird-populations-in-the-uk/wild-bird-populations-in-the-uk-and-england-1970-to-2024.

Wakefield, Susan. 2012. ‘Falconry as heritage in the United Arab Emirates,’ World Archaeology 44. 2: 280-290.

Weston, Phoebe. 2026. ‘How Demand for Elite Falcons in the Middle East is Driving Illegal Trade of British Birds,’ The Guardian, January 5: https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2026/jan/05/elite-falcons-middle-east-illegal-trafficking-trade-british-birds.

White, T. H. 1951 [2023]. The Goshawk, Alien ebooks.

Wild Animal Welfare Committee. 2025. ‘Wild Take Licences Come to an End,’ Wild Animal Welfare Committee, March 6: https://www.wawcommittee.org/news/wild-take-licences-come-to-an-end.

Leave a comment